A Look At The Heritage Area’s Historic (And Mysterious) Graveyards

There are two-dozen cemeteries located in or near Arabia Mountain National Heritage Area. Some go back to the Antebellum period, some are still maintained, and others we know surprisingly little about.

BOO! It’s that time of the year again when leaves starting changing colors, temperatures begin dropping, and Atlantans prepare their homes with spooky and ghoulish decorations for Halloween. There are plenty of good trick-or-treating locations in the National Heritage Area, but also no shortage of historic graveyards to learn about or respectfully visit. Cemeteries are also repositories of history, representing an important resource for communities. The land around us has been shaped to reflect traditional practices, values, beliefs and especially views on death.

Arabia Mountain National Heritage Area is home to 24 such cemeteries, some of which span most of our nation’s history. From small family cemeteries hidden in the woods, to large open church and city graveyards right by the road, these burial sites in the NHA encompass a wide range of time periods, settings, expressions and conditions, reflecting the complex history of the area. Unfortunately, although open to public visitation, many of the historic cemeteries in the Heritage Area have been neglected for decades, and some are accessible only via trail. While the Arabia Alliance staff can’t guarantee that any of these graveyards are haunted, the history and origins of some remain quite mysterious and require further archaeological investigation. The past has a way of speaking to us, especially in such sacred spaces. As William Faulkner famously wrote: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Below, please enjoy this “shortlist” of five of our most storied cemeteries.

Albert’s Grave Yard

One of the smallest and most mysterious burial plots is Albert’s Grave Yard, resting near the southernmost tip of the Heritage Area about a mile from Lorraine Trailhead. You won’t find any official signs or parking for this tiny graveyard located off of East Fairview Road SW. Park on the road shoulder (there’s plenty of space) and walk up to the entryway with a loose iron gate topped with a small cross and a stone archway, engraved with the words “Albert’s Grave Yard.”

The diminutive cemetery is completely enclosed by granite walls in a neat square, in which there are 8 Albert Family burials. There are 12 unmarked fieldstone graves within the walls, and a headstone outside the walls that belongs to a child named E. N. Sharp, born on July 16, 1862 and deceased on August 17, 1865. This site was an active burial ground from the 1860s until 1906. Other than this, very little is known about the Albert family and, in recent years, the site has clearly been neglected with many saplings growing up on the burial grounds. The placement of headstones on top of ledger stones in this graveyard is quite uncommon for the area.

An example of the headstones placed atop ledger stones at Albert’s Grave Yard.

Another tiny family graveyard is that of Mary Wade within the Davidson-Arabia Mountain Nature Preserve. To see it, take the Mary Wade Spur off of the Forest Trail from the Nature Center. Read more about it here.

Flat Rock Historic Cemetery

Shoemaker was a common surname in the Flat Rock community for many years.

This Flat Rock Historic Cemetery (sometimes called the “Historic Slave Cemetery”) is likely the oldest burial ground in the Heritage Area and certainly one of the oldest in DeKalb County. Not to be confused with the still-active Flat Rock Methodist Church Cemetery, the Historic Cemetery has graves dating back to the 1830s and was still in use nearly two centuries later up until the early 2000s. There could also be Native American remains at this site because, according to oral histories from Flat Rockers, the hill was a Muscogee burial ground before the ethnic cleansing of native people in the 1820s and ’30s, commonly known as the Trail of Tears. The most vulnerable cemeteries are those that have been forgotten to maps and memory. Almost all Native American burial gravesites are now completely lost and can only be recovered through archaeological investigation. Slave cemeteries, too (marked usually only by paired field stones aligned in an east-west orientation), are easily covered by overgrowth and therefore commonly overlooked and a frequent victim of development.

The entrance to the Historic Flat Rock Cemetery is located off of Lyons Road (not far from Lyon Farm). Started during Antebellum times, burial and funerary practice would’ve been one of the few rites afforded to enslaved individuals when even practicing faith in private was ill-afforded. This cemetery is also a rare example of a completely African American burial ground that has been used continually since the time of slavery to the present. Self-guided tours are available, but please be respectful of this hallowed and historical place. Grave markers in this site include rough, unmarked field stones, mortuary markers, obelisks, headstones, hand engraved tablets, concrete markers and quarried granite blocks.

Lithonia Historical African American Cemetery

A sign marking the entrance into the once-segregated African American Cemetery.

The Lithonia Historical African American Cemetery was started in the 1930s, likely then referred to as the “Lithonia Negro Cemetery.” Life in the area during this period was defined by segregation, as Jim Crow laws permeated every aspect of society. The burial of the dead was no exception to this rule as more cemeteries became openly segregated throughout much of the early 20th Century. The Lithonia African American Cemetery, just across from the historic Bruce Street School ruins, served Lithonia’s Black population for several generations. While it doesn’t look that expansive from Bruce Street, the graveyard is spread out over several acres, some of it badly overgrown and polluted. Notable figures interred there include the Bruce Street School Master Cook Ada Anderson Beck, and Civil Rights icon Lucious Sanders, the first Black board-member of DeKalb County Recreation, Parks & Cultural Affairs.

Lithonia City Cemetery, a burial ground for primarily European Americans, was active at the same time as the Lithonia African American Cemetery. Located just a couple of miles from each other, the the state of these two sites reflect the effects of segregation on burial grounds even today, as the African American graveyard is not nearly as well maintained or landscaped as the City Cemetery, where lie the remains of some of the richest families in Lithonia’s history, including the Davidsons who owned Arabia Mountain and the largest quarrying operation in town.

Located at the once-segregated Lithonia City Cemetery, the Davidson Family Grave marker is as large as the entrance sign into the African American Cemetery.

While both of these graveyards are now owned by the City of Lithonia, the difference in appearance and upkeep is evidence of structural racism from the past impacting the present. A surprising majority of old graveyards are also neglected because they were once owned by individuals. Over the years, sometimes ownership of the land becomes unclear or fragmented, and maintaining an inactive burial ground is quite costly. Without state or local resources, many such cemeteries fall into disrepair and become partially or completely overgrown and forgotten.

Monastery of the Holy Spirit Monk Cemetery

All the monks who’ve passed away at the Monastery of the Holy Spirit are buried in the Monk Cemetery.

While many of the grave sites in the Heritage Area are predominantly protestant, the Monk Cemetery at Conyers’ Monastery of the Holy Spirit represents unique ecclesiastical burial practices. This cemetery is reserved only for monks of the Order of Cistercians of the Strict Observance (OCSO). The deceased in this small cemetery tucked behind the Abbey Church are laid into the ground wrapped in a shawl instead of a casket, and grave markers contain only death dates. Cistercians believe that one’s death, or entrance into heaven, is their true birthday. While the Monk Cemetery is not open to the public, it can be accessed during a monthly Highlights and Insights Tours of the Monastery. Please check the Arabia Alliance Eventbrite page for availability.

Brother Callistus talks about the Monk Cemetery during a Monastery tour.

The Monastery of the Holy Spirit is also home to Honey Creek Woodlands, the largest combination conservation green burial ground in the country. This is the newest burial ground in the NHA. At Honey Creek, all faiths and nonbelievers have their remains interred in the most non-invasive and natural way possible—meaning no embalming and only biodegradable caskets or urns for ashes—with graves and markers blending in with the landscape. In addition to supporting the Monastery’s operations, 160 acres of Honey Creek land along the South River is dedicated to permanent protection. While not a public park, tours of Honey Creek Woodlands can be arranged here.

Additionally, the Monastery’s 2,000-plus acres once would’ve comprised several plantations during the Antebellum period. The remains of a slave cemetery have been discovered on these grounds. Using ground penetrating radar, 40 graves were located along with headstones and fieldstones. However, this site is not open to the pubic and requires further historical research.

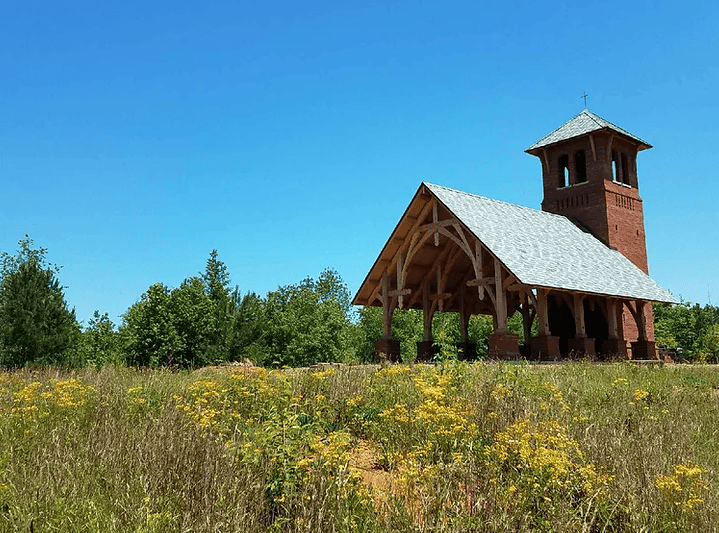

The iconic open-air chapel at Honey Creek Woodlands.

Stanley Cemetery

The importance of the family unit is repeatedly evident in cemeteries found in the Heritage Area. 10 of our 24 graveyards were, at one point, private family cemeteries, and 8 of these originated in the 19th Century. The Stanley Cemetery, located by Alexander Lake at Panola Mountain State Park, is a great example of a burial site that started as a family graveyard. An unpaved footpath leads from Alexanders Lake Road to the entrance with a decorative cemetery fence. Some of the predominant family names buried here include Stanley, Berry, Browning and the Alexanders, including Ed Alexander who sold his family land to the State of Georgia to help create the Alexander Lake entrance into Panola Mountain State Park.

An interesting range of grave markers exist at Stanley Cemetery, from small square headstones flush with the ground to engraved obelisks and even some natural granite outcrop that was used as a burial marker for the Alexander Family by fixing a bronze plaque to it (pictured above). However, like the majority of burial sites in the Heritage Area, neglect has taken its toll on this place. The area is overgrown with plants and needs to be cleared to prevent further deterioration of burial markers. The burial ground lies just outside the bounds of the State Park and, as mentioned earlier, without extra resources, many do not have the funds to maintain historic burial lands.

A neglected section of Stanley Cemetery.