Honey Creek Woodlands: A Look Inside The Largest Conservation Green Burial Ground In The Country

Started in 2008, Honey Creek Woodlands at The Monastery of the Holy Spirit has protected land and waterfront while also offering natural burials to more than 2,000 deceased.

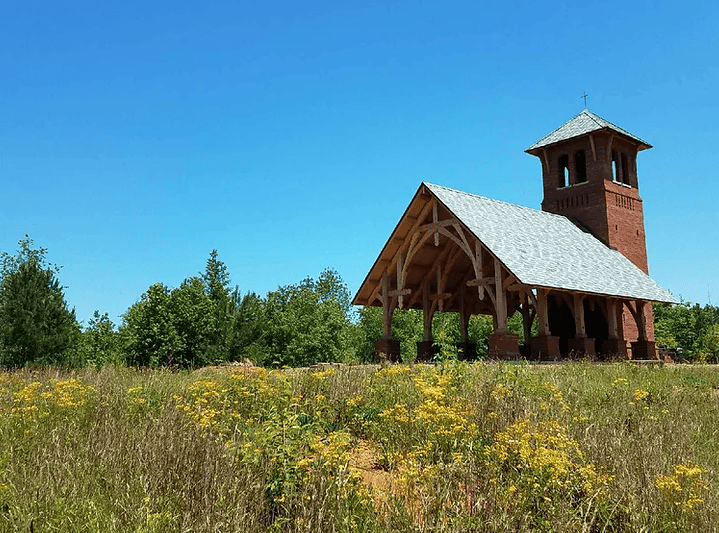

A cemetery by a church is nothing unusual—but a cemetery in a nature preserve? That’s the concept behind Honey Creek Woodlands, a combination green burial cemetery and conservation space on the grounds of the Monastery of the Holy Spirit (MOHS). The Monastery property designated for burial contains protected wetlands, native hardwood forests and a stunning, outdoor chapel featured in Southern Living on a list of “The South’s Most Beautiful Chapels.” With 160 acres dedicated to permanent protection and interring remains, Honey Creek Woodlands is the largest conservation burial ground in the country.

A Different Kind Of Cemetery

“When you’re walking out there, it just looks like you’re in the woods and you don’t even realize that you’re in a cemetery—until you look closely, and that’s the point,” said Father Francis Michael, Abbott of the Monastery of the Holy Spirit from 1994 to 2016 when the natural burial ground and preserve was first conceived. With in-ground grave markers, plots at Honey Creek Woodlands blend in seamlessly with the surrounding landscape; and bodies are laid to rest in a biodegradable shroud or casket and cremated remains in a biodegradable container. The result is a much greener and cheaper interment.

A grave in the pine forest.

For decades, the Trappist monks at MOHS generated most of their income from their large tract of land, first from raising cattle and livestock and later from timbering. However, as an avid naturalist, Francis Michael didn’t like the detrimental effect of clear-cutting or thinning forest. “We were messing up the ecosystem and all the critters were going to disappear,” said Francis Michael. “When I became Abbott, we clear-cut thirty-five acres, but I was looking for some other way to use those acres rather than replant them with more pine. So when [Arabia Alliance Board Treasurer] Kelly Jordan told me about this idea of a natural conservation cemetery, I brought it to the community and my basic argument was that it would be good to have some diversity and not more pines.”

The Man Behind Natural Burial

To help grow this green conservation cemetery, Francis Michael reached out to Joe Whittaker, a volunteer at the very first such cemetery in the country at Ramsey Creek Preserve in South Carolina. “I love swamps; they’re just so still and peaceful,” said Whittaker, a Carolina native. “I used to joke, ‘When I’m gone, just drag my body out to the swamps and let the gators recycle it.’ But that was my dream, a natural burial, and everyone said that’s not possible.”

Joe Whittaker, Head Steward of Honey Creek Woodlands from 2008-2018.

Fifteen years ago, Joe Whittaker had no experience in burial and, although a fan of the outdoors, none in conservation either. He had a marketing background, and it was a radio show that piqued his interest in green interment. “I heard a story on NPR about people getting buried on hiking trails and I couldn’t believe that they were in Westminster, South Carolina,” recalled Whittaker. “I was like, Man, that’s down the road from me!” Whittaker visited the group running the Ramsey Creek burial preserve, a small organization called Memorial Ecosystems. “We clicked immediately and I started helping them,” said Whittaker. “It was really small-scale, but it got a lot of media attention. These burial grounds monetize conservation, which is very hard to do.”

Making A Cemetery

Opened on Earth Day in 2008, Honey Creek Woodland’s first year saw just twelve burials. Whittaker joined as Head Steward and recognized the many challenges in transforming the Monastery’s muddy, recently deforested tract into a natural-looking green space. “The hardest aspect of the burial business is starting a new cemetery,” he said. “No one wants to be first.” Using his marketing expertise, Whittaker visited a lot of parishes in the Atlanta metro area, believing word of mouth among the Catholic community the best way to initially grow the natural burial ground. “We’re open to all faiths,” said Whittaker. “And I would tell people, ‘This may not be the thing for you, but when you come to a funeral here you’re going to talk about it.’”

Whittaker’s strategy paid off. Nearly fifteen years later, Honey Creek Woodlands performs five burials a week with 5,000 plots sold and 2,100 occupied. The natural cemetery has interred people’s ashes shipped from all over the country and sometimes even overseas. “This was a special place for a lot of [international] people because this had been the monastery where they came to for retreat,” said Whittaker. “And that’s still all from word of mouth. We don’t pay for advertising.”

The success of the cemetery has surprised even Francis Michael. Although the MOHS monks are well known for their homemade fudge and biscotti and, now retired, bonsai garden, the burials at Honey Creek Woodlands have brought in far more revenue. “When I argued for this as Abbot, I said if we could simply make as much money on the cemetery as we did on the pines after 30 years, we’d break even and have a different habitat,” he said. “And now we’re making more in one year of burial than we would waiting 30 years to clear-cut.”

Preserving Nature And Memories

Although public hiking isn’t allowed, Honey Creek Woodlands is open to anyone who has a loved one buried there. All profit goes back into the Monastery and the cemetery, which has successfully restored natural flora and fauna and permanently preserved nearly a mile of South River waterfront. In addition to plant and animal life, this new land also preserves people’s histories. “Years ago, we had a young couple who lost a baby named Grace,” said Whittaker. “And every time they visited, the bridge over Honey Creek was flooded. The father of Grace came to me and said, ‘I’m in big construction projects; I can build you a bridge.’ They raised all the money to build us a beautiful bridge. And there’s a plaque on it now that says, ‘Bridge to Grace.’ Most people think it’s the word “grace,” but for that family, it’s literally their bridge to Grace.”

The dedication of the Bridge to Grace.