How The Yarbrough Family Preserved Panola Mountain

Before it was a declared a State Park in 1974, Panola was privately owned by John Yarbrough, a local motor man who fell in love with the mountain.

It’s hard to believe but Panola Mountain State Park (PMSP), the only National Natural Landmark in Metro Atlanta, was once considered so unvaluable it was given away more than once in its history. Never quarried because of the poor quality of its stone, Panola Mountain sat largely untouched and unnoticed throughout its history. That all changed, however, in the 1930s when an Atlanta-area businessman named John Eugene Yarbrough saw the mountain with its lunar-like landscape and fell in love.

From Motors To Mountain

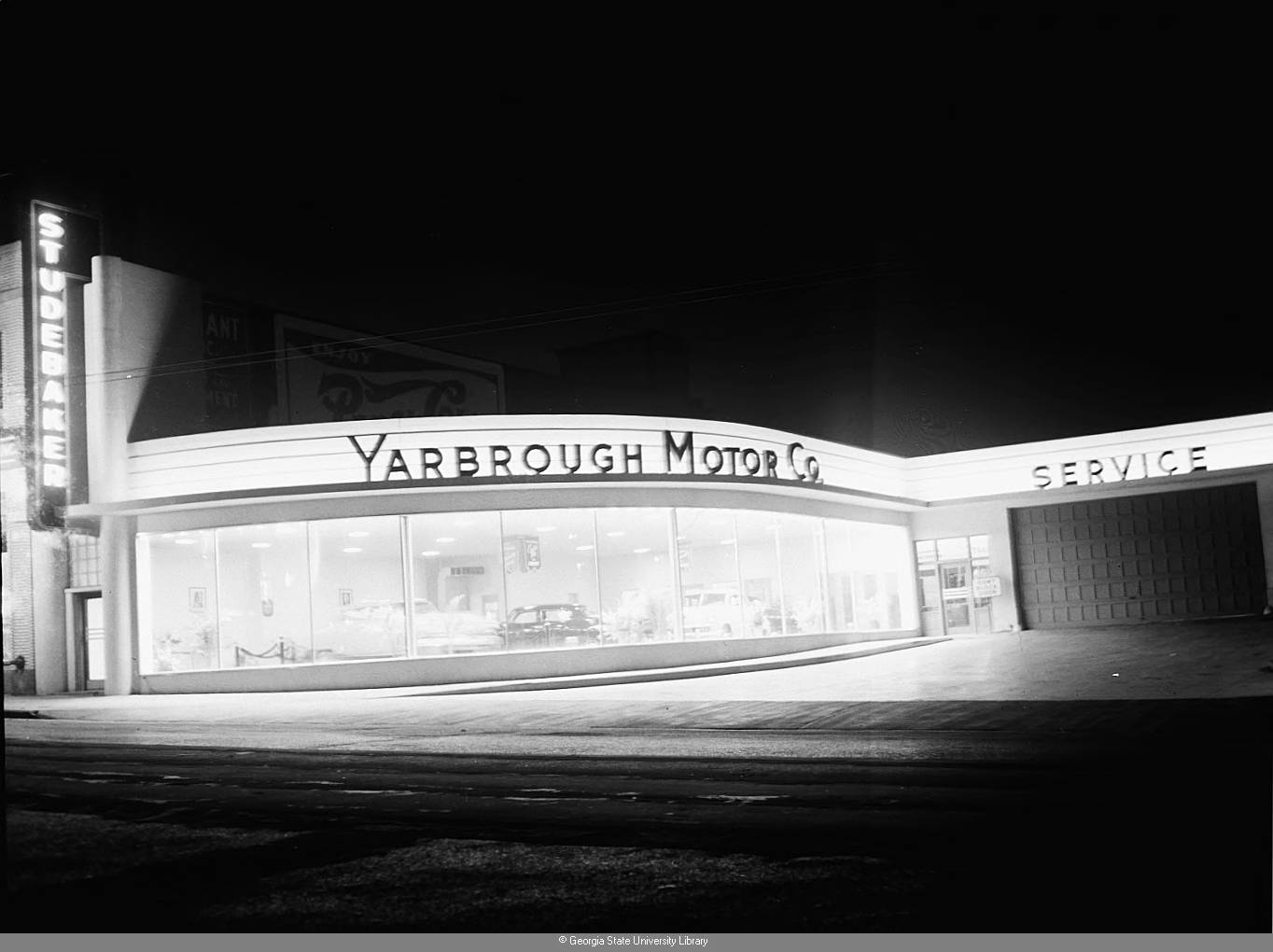

Born in 1886 in Williamson, Georgia, Yarbrough had an early interest in cars that flourished into the successful Yarbrough Motor Co., which specialized in selling Studebakers in Atlanta. In 1933, during the doldrums of the Great Depression, Yarbrough bought Panola Mountain from his new brother-in-law Dr. James Addison Bell and his wife Blanche, a wealthy couple from Decatur. Yarbrough purchased the land as an investment opportunity, waiting to develop it until after the economy recovered.

The Yarbrough Motor Co. from 1947. (Digital Archive of Georgia)

However, things didn’t go quite as Yarbrough planned. Panola Mountain is a monadnock—a large, solid rock mass, millions of years old, unideal for building upon. Once the Depression and then WWII were finally over more than a dozen years later, Yarbrough, whose five kids had grown and begun to have children of their own, decided to develop the land around Panola Mountain in a way it had never been used before: for fun and leisure.

An ad for the Yarbrough Motor Co. with Lanier (left) and Jack (John Jr.) at center. (Digital Archive of Georgia)

Creating A Country Getaway

In the early 1950s, Yarbrough dammed the stream on the south side of Panola Mountain, creating what is now called Mountain Lake. He spread out a sandy beach on the shore, stocked the new pond with bass and other fish, and constructed the hexagonal pavilion that still stands today. Around this time, Yarbrough also had built a big house on the bluff overlooking the new lake along with three cabins so his five kids—(in order of birth) Jack, Walter, Lanier, Mary Jenelle, and Ella “Gregg”—could enjoy the comforts of a rustic country getaway.

Good times at the lake. Jenelle and her husband Hugh stand center background. Lucille and husband Jack Yarbrough sit on the far left next to Gregg and her husband Mo Phelps with Paula Galland in between them. Bottom row closest to the camera sit Hugh and Jenelle’s 3 kids: John, Priscilla, and Nancy Manning. (Panola Mountain State Park)

“Everybody used it to entertain friends—there were always people other than family who were coming to be entertained,” said Priscilla Manning Jenkins, John Yarbrough’s granddaughter and daughter of Jenelle, who spent weekends and summers as a child at the mountain retreat. According to Priscilla, the family had a blast, saying, “[My Brother] John and I were just talking about how much fun it was. No TV. No phones. We just played outside—we had the run of that place.”

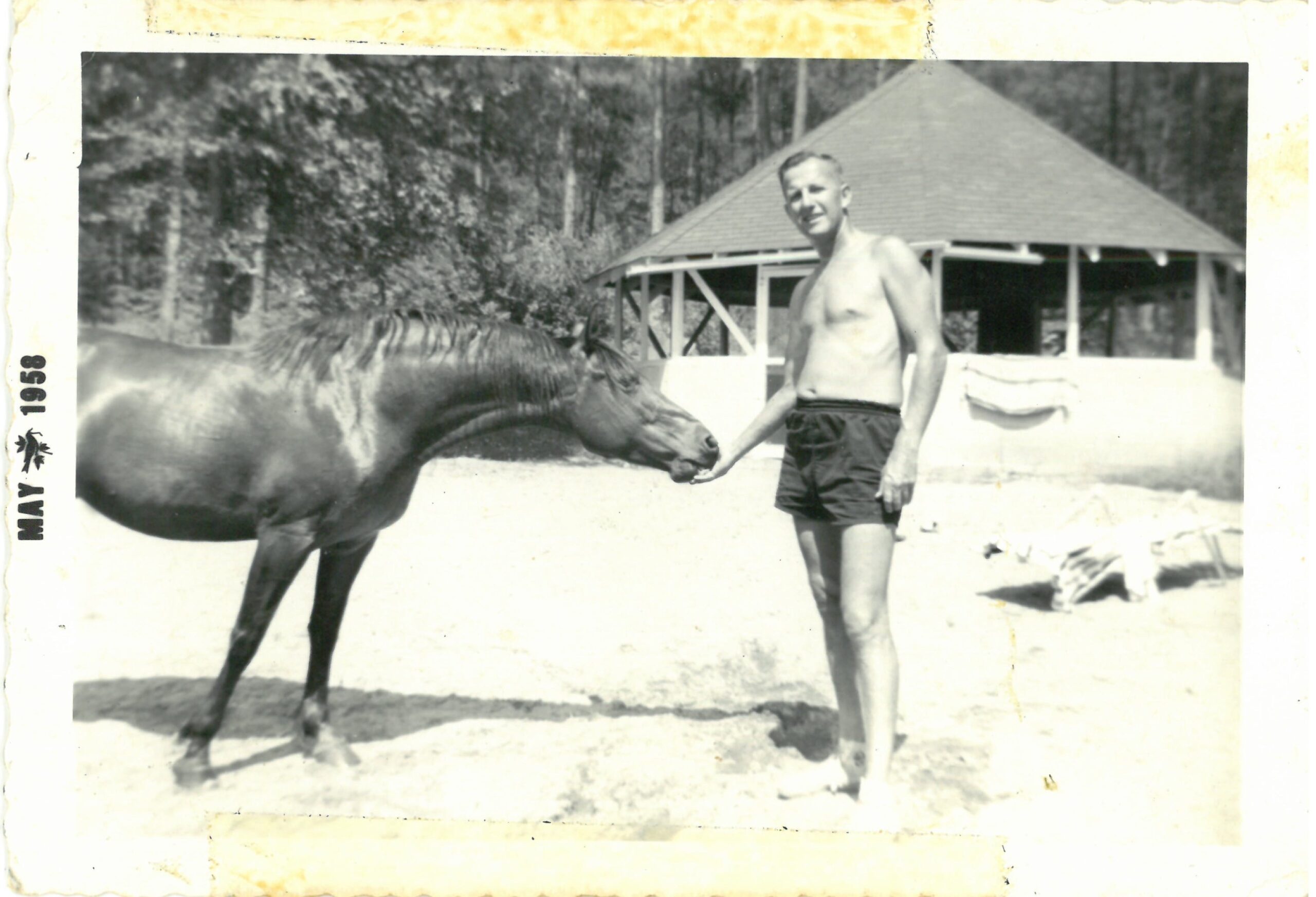

Priscilla’s father Hugh particularly enjoyed horseback riding while at Panola, even once riding his horse Duchess to the summit and back.

“Uncle Hugh” with Duchess, enjoying a sunny day at Mountain Lake. (Panola Mountain State Park)

“Daddy John [Yarbrough] originally bought Duchess for Priscilla, thinking every little girl wanted a horse, not knowing that she was afraid of horses,” said Paula Galland, Priscilla’s cousin who grew up spending summers with the Yarbroughs at Panola. “He would make us ride Duchess. If we refused, we had to eat a prune. Duchess didn’t like us any more than we liked her.”

Sometimes the fun-having went a little too far. One Fourth of July in the late ’50s, Priscilla’s brother John and a friend were throwing firecrackers into the pavilion. One bounced out the back into the pinewoods behind, which, on a dry summer day with plenty of pine straw, soon caught fire. “He was scared to death,” laughed Priscilla about her brother’s reaction. “But he ran and rode out and got the forest rangers. They came in and, all night long, were digging trenches and spraying water and finally got it stopped.”

John was quite impressed by the firemen who worked through the night to contain the blaze. This incident inspired him to later join the National Forestry Service, doing controlled burns of pinewoods in south Georgia near the Florida line.

One of the old Yarbrough cabins (Hugh and Jenelle’s) that was demolished after the land was sold to the state. (Panola Mountain State Park)

Family Tragedies

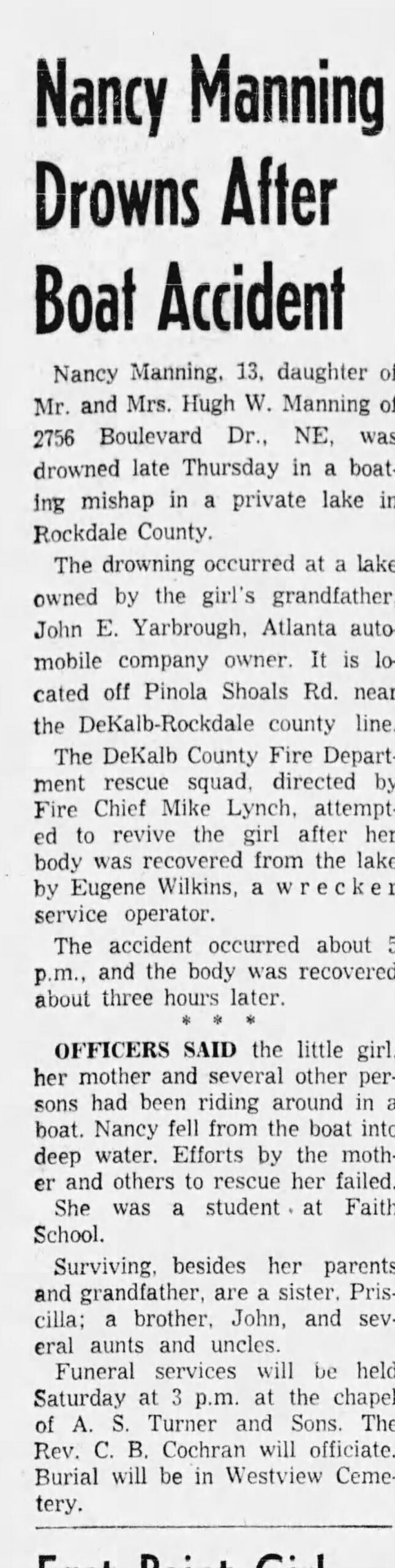

It wasn’t always sunny memories, however. One sweltering mid-July day in 1954, Hugh and Jenelle were at the lake with their family, swimming and suntanning. Priscilla’s sister Nancy climbed into the little family rowboat with some family friends. Then, out in the middle of the lake, Nancy suddenly bolted straight up and tumbled out of the boat into the water.

Priscilla watched in horror from the shore as her mother ran toward the lake after her sister. “I was only 7…we were all swimming at the beach,” said Priscilla. “She had cerebral palsy, and she had frequent seizures. She stood up in the boat, had a seizure, and fell in. And she didn’t come back up.”

Nancy’s drowning made news in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, which reported at the time that: “The DeKalb County Fire Department rescue squad, directed by Fire Chief Mike Lynch, attempted to revive the girl after her body was recovered from the lake by Eugene Wilkins, a wrecker service operator.

“The accident occurred at 5 p.m., and the body was recovered about three hours later.”

It was just two months later when tragedy struck again. Priscilla lost her uncle Jack, the eldest of the five Yarbrough siblings, who died unexpectedly in September 1954 of a heart attack. He was only 43 years old. According to his obituary, “[a] member of the family said he had been ill for about three months. Mr. Yarbrough last year succeeded to the presidency of the company founded by his father, who survives him.”

Nancy’s drowning and Jack’s sudden passing left its mark on the family. “Because of what happened, it was really hard for my mother to go back down there,” said Priscilla, remembering that day 70 years ago now. “Still, we continued living almost every summer out there all summer long.”

Photos from this period show the family still having good times at their monadnock escape. However, these same images also reveal a roped-off swimming area around the beach. “The photos with boats were before my time,” said Paula Galland. “After Nancy drowned, Daddy John (John Yarbrough Sr.) would not let boats on the lake. We had a roped-off swimming area, which we had to stay in. I think we were told water moccasins were in the other parts of the lake and to stay away.”

The pavilion and beach at Panola’s Mountain Lake with a roped off section for swimming, taken after Nancy’s passing. (Panola Mountain State Park)

The early ’60s would bring another hard stretch for John Yarbrough and the family. Lanier Yarbrough (John Sr.’s youngest son) was a WWII veteran who returned from the conflict with a lot of trauma and bad memories, what we would now call Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. In 1961, after an acrimonious divorce from his wife Netty and years of drinking to cope with his demons, Lanier broke into Hugh and Jenelle’s cabin and stole a .22 rifle. He then entered the shed outside and took his own life with the rifle. He was 44 years old, his body discovered by the property caretaker Roy West.

The following year, Daddy John Yarbrough, who’d created this Panola Paradise for his family, passed away at his home, aged 75. His obituary said that Yarbrough “had been an Atlanta resident 40 years [and] was a graduate of Georgia Institute of Technology and was a member of Druid Hills Methodist Church.”

The year after that, in 1963, his last surviving son, Walt—a dentist with a wild side and a penchant for race cars—crashed his car into a tree on Highway 155 not far from Panola. He was driving a Studebaker Avanti, a car no doubt from the Yarbrough Motor Co. None of John Yarbrough’s boys lived to see 50. And in the 1960s, with most of the grandchildren grown, the cabins Yarbrough built for his progeny began to gather dust, cobwebs and bug carcasses.

Mountain For Sale

The Yarbrough sisters, Gregg and Jenelle, who helped save Panola after Daddy John died. (Panola Mountain State Park)

After John Sr.’s death, Panola Mountain was willed to 12 members of his family. “Some in the family wanted to sell it to a developer,” recalled Priscilla. Some of those early discussions about what to do with the property got divisive and, at times, explosive. “But my mother [Jenelle] and her sister [Gregg] really had controlling interest in it. They said that their father was an environmentalist—and it could not possibly have been anything else, for him than a state park.”

In 1967, that dream began to form into reality when the remaining family members entered discussions with James Mackey from the Georgia Conservancy. The Conservancy was impressed by the pristine environment on the mountain, finding extensive colonies of at least four threatened and endangered Georgia plant species. In May 1971, with the help of the Georgia Conservancy, a deal was finalized in which the state bought the area for $200,000, establishing the first conservation park in Georgia.

Four years later, in 1974, then-Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter spoke at the official opening ceremony of Panola Mountain State Park. Half a century after that, Panola remains the only untouched monadnock environment in the metro area—and just as pretty as it ever was.

Governor Jimmy Carter during the Panola Dedication Ceremony in 1974. (Panola Mountain State Park)