All About That “Red Stuff” – Diamorpha At Arabia

The illusive red succulent returns this spring with its white flowery bloom. What do we know about it and why is it so rare?

Each spring in the Heritage Area, rock outcrops turn bright red with the emergence of diamorpha (Sedum smallii, synonym Diamorpha smallii), also known as elf orpine and Small’s stonecrop. This rare succulent plant in the Crassulaceae family grows in solution pits, vernal pools and cavities in the expanses of open rock surface. For several weeks, the plant dawns white flowers in bloom, mixing white into to the carpets of red. Although it can be found elsewhere, the Arabia Mountain National Heritage Area is known for its abundance of the plant and draws in visitors from all over eager to see it. So what do we know about diamorpha and why is it so rare?

Diamorpha often grows in large patches, populating solution pits on rock outcrops which are also home to countless other organisms like other plants, lichens, mosses, insects, arachnids and amphibians.

The Southern Piedmont’s Rare Gem

Diamorpha belongs to the Sedum species of plants, which are also known as stonecrops. These plants are succulents, possessing thick, fleshy sections which retain water, allowing them to survive in drought conditions, such as cacti and aloe. Stonecrops tend to grow in overspreads, carpeting their surface, and are popular in landscaping for this reason.

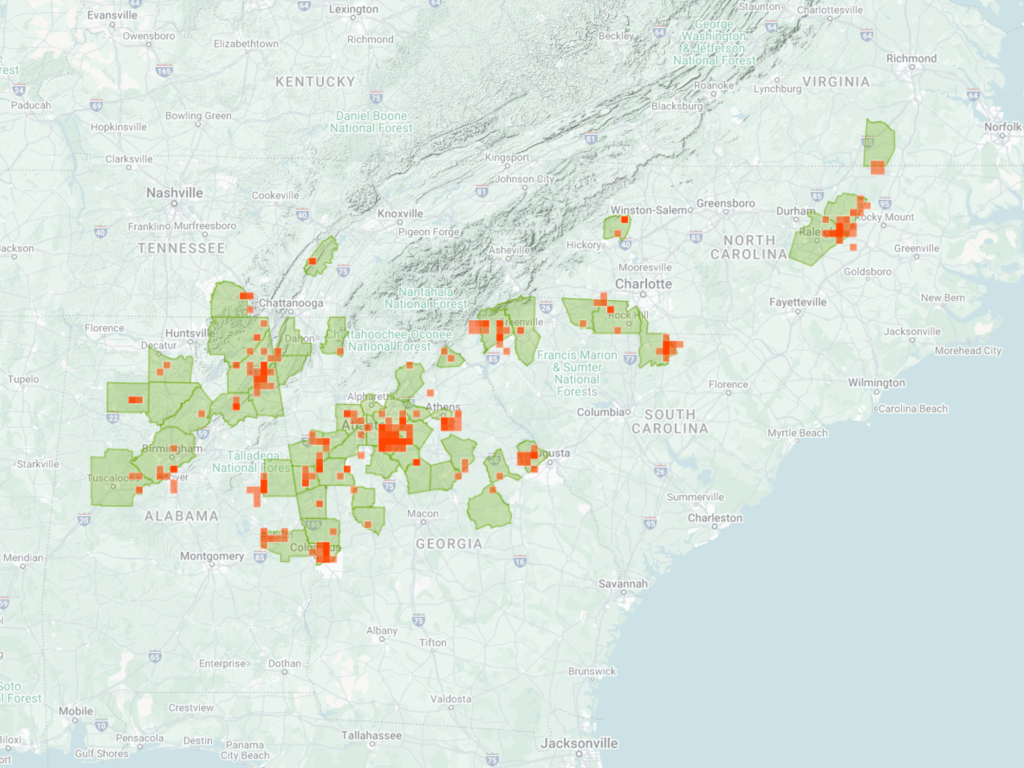

The hearty red succulent is endemic to the Piedmont Region of the Southeast, with populations noted in Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, the Carolinas and Virginia. The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation lists elf orpine as an endangered species. As demonstrated by the map below, the Arabia Mountain NHA—with Panola Mountain State Park and the Davidson-Arabia Mountain Nature Preserve—has the densest populations of this rare red gem of a plant.

Diamorpha user-submitted observations map, via iNaturalist (inaturalist.org).

When dormant, diamorpha is much less striking in appearance in contrast from its springtime bright red.

Diamorpha is a product of its environment, adapted specifically for survival and reproduction in the Southern Piedmont Region’s outcrop environments where, during the summer, the rock’s surface temperature can exceed 100°F. It primarily populates vernal pools, seasonal puddles of water contained by rock or dirt, and solution pits, thin patches of dirt isolated on rock outcrops, where it has enough resources to grow and survive. The plant stays hidden most of the year, emerging in late winter, blooming for several weeks in early spring and then going dormant once temperatures rise higher towards the end of the season. When dormant, diamorpha loses its bright red color and takes on the appearance of little brown stems sticking up from the ground while holding on to its seeds to avoid them from drying up during the hottest months of the year. The seeds drop and begin to germinate in fall. These particular habitat conditions are what make diamorpha so rare.

Diamorpha growing next to hair cap moss (Polytrichum commune) and eastern prickly pear (Opuntia lata), two other plants which are adapted to the harsh conditions of rock outcrops.

A Unique Partnership

According to a 1997 article, “Reproductive ecology of granite outcrop plants from the south-eastern United States”, by University of Georgia Biology and Ecology professor Robert Wyatt, diamorpha exhibits a rare pollination relationship with several species of ants. Ants do not usually carry out the roles of pollinators and rarely pollinate plants, making this relationship quite unusual. In fact, many ant species secrete an antibiotic chemical which protects them from fungal and bacterial diseases, which usually kills any pollen they may have on them. However, species Formica pallidefulva (formerly Formica schaufussi) and F. subsericea don’t seem to exhibit this characteristic and have shown to consume bits of nectar produced by elf orpine and transport its pollen.

Besides these ants, bees and flies also pollinate the plant. Watch a patch of diamorpha closely and you will likely see ants and other insects navigating through the mini-forests of rose-red succulents.

Visit the rock outcrops of the Heritage Area in late March and April to see diamorpha’s stunning white bloom!

A Debated Taxonomy

Diamorpha’s current binomial nomenclature (or “scientific naming”) of Sedum smallii and its entire taxonomy has been a point of debate among botanists. In an article from a 1988 issue of SIDA, Contributions to Botany, Robert L. Wilbur of the Department of Botany at Duke University argued that the naming of Sedum smallii is inaccurate and that the plant shouldn’t even be considered a sedum due to its structural differences. In this article, Wilbur explained that the assigned genus of “Sedum” was the result of long-lasting confusion faced by botanists as a result of an initial misidentification.

Granite stonecrop (Sedum pusillum), Michaux’s plant which diamorpha was confused with due to similarities in its appearance, at Panola Mountain.

Diamorpha was initially observed by Thomas Nuttall, an English botanist and ornithologist, who in 1816 followed in the footsteps of French botanist André Michaux to a rock outcrop in Kershaw County, South Carolina where Michaux first observed the crassulaceae plant Sedum pusillum, also known as granite stonecrop or Puck’s orpine. Nuttall erroneously assumed that he had encountered the same plant (although studies have shown that the two plants are related), a mistake that led to a longstanding confusion regarding the proper identification of the plant, but later renamed its genus to Diamorpha.

The distinction between the two different species only became evident in 1875 when botanist Asa Gray observed both diamorpha and granite stonecrop at Stone Mountain during a trip with his wife through the Atlanta area. This launched a series of renamings of the plant by various botanists, which after years of back-and-forth changes due to disagreements, ended with Sedum smallii (with Diamorpha smallii used as a synonym), named after botanist John Kunkel Small, an expert on Southeastern flora.

If you’re reading this in April, the diamorpha is still in bloom and visible on most rock outcrops in the Heritage Area, so get out there and see it for yourself while its still there!