A History Of The Klan At Stone Mountain

The KKK was reborn on Stone Mountain in 1915 and Klan rallies continued in the town until the late ’70s.

DeKalb County park ranger Horace O’Kelly still remembers the annual Ku Klux Klan rallies that would meet in Stone Mountain and march through Shermantown, a historically Black neighborhood nearby.

“They usually came through on a Saturday,” said O’Kelly, who spent his adolescence in Stone Mountain and graduated from the high school there in 1983. “They started by the cemetery and marched through downtown and turned on Fourth Street all the way down to the park in Shermantown and burned their crosses.”

The Long Reach Of Jim Crow

O’Kelly’s memories are part of a well-known history of the Klan at Stone Mountain, which has become the state’s most visited tourist spot. Carved into the mountain’s east-facing side is a 90-foot-tall testament to this historical connection, a “Memorial to the Confederacy” in the form of a large bas relief of three Confederate figures: Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, and Jefferson Davis, the Confederacy’s first and only president.

Although a few miles outside of the National Heritage Area, Stone Mountain shares a common racial and social history with Lithonia and Arabia Mountain farther south. For many Georgians, it’s well known that in 1915 the Ku Klux Klan was reborn on Stone Mountain when a group of prominent White locals burned a cross on top of it ushering in a new era of both state sanctioned and extrajudicial racial terrorism, torture and lynchings known as Jim Crow. One of those men was James Venable, future mayor of Stone Mountain from 1946-49 and later an Imperial Wizard of the National Knights of the Klan. However, what is generally less known is that these mountaintop cross burnings continued until 1962, and annual Klan rallies still marched through the streets of Stone Mountain as late as 1978.

Klansmen gather for a rally in 1921 or ’22 at an unknown location. (National Photo Company)

O’Kelly was just a freshman at the local high school in the late ’70s. He lived with his mother right in front of the pasture where these rallies occurred in Shermantown, a resilient Stone Mountain community named by Freed People of Color for Union General William T. Sherman. During the Civil War, Sherman’s March to the Sea liberated many Black Georgians and became the nation’s largest emancipation event.

“They marched past us, and we could see them from my mother’s house,” recalled O’Kelly of the summertime national Klan Rallies in the ’70s. “They burned the cross in that field. I could hear them all night, [shouting] ‘White power!’ Somebody would speak, and all you would hear was: white power, white power. They’d be in their robes so we couldn’t identify them. You could smell remnants of the wood burning weeks after.”

Horace O’Kelly lives in McDonough about a half-hour from Stone Mountain where he grew up.

One of these rallies that O’Kelly describes can be seen in the 1978 PBS documentary The New Klan: Heritage of Hate. At the 16-minutes mark of this hourlong investigation, James Venable is interviewed by PBS journalists while he watches others place crosses in the earth between Stone Mountain and Shermantown. Later, at around the 37-minute mark, the Klan rally commences with remarks from infamous white supremacist and politician David Duke before a dwindling audience of only a few dozen. WARNING: This video contains hate speech and offensive language and images.

A Masked History

The original Klan was founded in 1865, the same year the Civil War ended, and had been largely stamped out by the mid-1870s during Reconstruction under President Grant. However, a new generation would bring a renewed surge in racial white terrorism. 1915 would prove an explosive and foundational year for the creation of Jim Crow. That year saw the release of “The Birth of a Nation,” the country’s first blockbuster, so to speak, a white supremacist fantasy about the Confederacy, the Klan and Reconstruction. It was the first American 12-reel film ever made and the first screened in the White House, where President Woodrow Wilson reportedly said, “It’s like writing history with lightning.”

That same year in Georgia also witnessed the lynching of Leo Frank in August, a Jewish Atlantan wrongly convicted of the murder of a 13-year-old, and just months later on Thanksgiving night, the rekindling of the Klan atop Stone Mountain. Dressed in robes and hoods and led by a Protestant Preacher named William Joseph Simmons, the men ceremoniously torched a 16-foot cross that sparked a new era of domestic white terrorism against the Black populace. At the time, the mountain was owned by Sam Venable, one of the biggest names in Atlanta that had owned and operated quarries at Stone, Pine and Arabia Mountains. That night, Sam became a member of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, or Second Klan (as it became known), as did his nephew James.

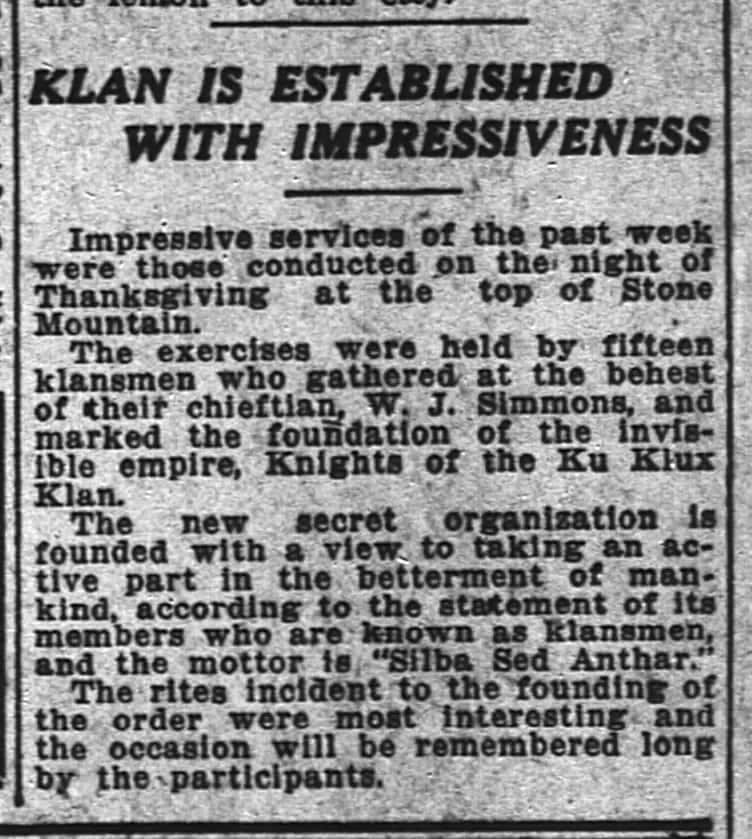

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wrote about the Klan revival in 1915, describing the event in eerily positive terms as “impressive” and “most interesting.”

It wasn’t just Stone Mountain damaged by this renewed racial conflagration burning across the country. James Venable was born in Stone Mountain but attended Lithonia High School just a few miles south with Nathan Bedford Forrest III, the grandson of Nathan Bedford Forrest, founder of the original 1865 Klan. Ergo, Lithonia (then a bigger city than Stone Mountain) was no different.

Throughout the 1930s until the late ’40s, the Klan had a strong presence in the NHA’s historic heart at Lithonia, holding regular rallies that marched down Swift Street, then one of the few mixed-race streets in town, and burning crosses in the city park. Howard Lee was one of these residents on Swift Street. At the time, he would’ve been a student at the historic Bruce Street School, DeKalb County’s first public school for Black students.

Lee would later go on to become the first Black mayor of Chapel Hill, North Carolina and later the first Black member of a governor’s cabinet in the South. In his autobiography The Courage to Lead, he wrote about the Klan in Lithonia:

“Ku Klux Klan rallies were a frequent occurrence in Lithonia. Every Friday afternoon, droves of Klansmen would parade through town in cars and pickup trucks, waving guns as an intimidation tactic aimed at keeping blacks in their place. At the end of the parade, the hooded figures would gather a few blocks east of the center of town in a vacant field near our house on Swift Street. They would listen to hate speeches that would whip the crowd into a high emotional state. The rally always ended with the burning of a gigantic, gasoline-soaked cross. Occasionally, we would hear that some black person had been attacked and beaten during the late hours. Sometimes they would just plant and burn a small cross in somebody’s yard as a warning.”

Howard Lee (center without helmet) playing on the first Bruce Street Football Team while the Klan was still prominent in Lithonia. (Howard Lee)

Life In The Twilight Of The KKK

A generation after Howard Lee’s time in high school, events like the Civil Rights Movement and the Voting Rights Act had changed Lithonia and Stone Mountain some. However, the Klan still persisted and life in small towns like Stone Mountain was still in a period of transition in the late ’70s and early ’80s.

O’Kelly still remembers how he felt when his mother moved him and the family from rural Rockdale County, where there wasn’t much of a Klan presence, to the birthplace of the new Klan right next to Stone Mountain. “I used to joke with my mom, ‘You moved me up here for this?'” recalled O’Kelly. “At first, it was kind of scary. I knew of racism, but it was a learning experience. Back then, Stone Mountain was predominantly white.”

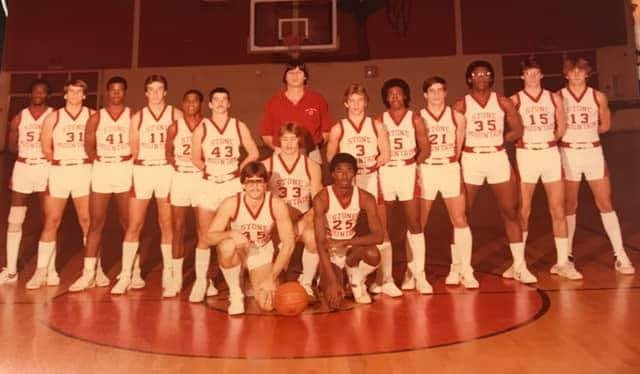

Horace O’Kelly was number 25 (front row, right of center) and the star of the Stone Mountain High Basketball Team.

Like many of the residents of Shermantown, O’Kelly learned cleverly to resist by thriving and co-existing next to the stoney heart of the Georgia Klan. Although constantly in the shadow of Stone Mountain and these cross burnings, no major race incidents occurred between Shermantown and Stone Mountain Village.

“My friends and I were able to adapt to it,” said O’Kelly, who echoed other Shermantowners’ sentiments about race relations in Stone Mountain at the time. “We had a couple of race incidents, of people using the N word at school.”

By then, Stone Mountain had its first Black Police Chief, James Rivers, who had started as the town’s garbage collector. 1978 also marked the last year a national Klan rally marched through the streets of the Stone Mountain and Shermantown. (Shrinking national membership and interest likely played a role.) About two decades later in 1997, the town would elect its first Black mayor in Chuck Burris. In a strange twist of history, before becoming mayor, Burris had attracted an unlikely supporter when he ran for city council: James Venable, the former Imperial Wizard. Burris even ended up buying the historic Venable house when Sam died in 1993 and lived there during his mayorship.

As for O’Kelly, after high school graduation, he went on to work as a respected Park Ranger for DeKalb County Recreation, Parks and Cultural Affairs, where he’s been busy for 30 years now. Today he volunteers his time with the County at Lucious Sanders Recreation Center in Lithonia and with LifeLink of Georgia. He still misses his days playing basketball at Stone Mountain High School where, in spite of the history and presence of the Klan always nearby, he made many friends, Black and White. “I cried at my high school graduation,” O’Kelly said. “I had one of the best times of my life then.”

O’Kelly (back row and third from left) attended his 40th class reunion in 2023.