The Darker Side Of DeKalb

Stories of lynching, mob violence and Jim Crow-era White Terrorism are part of DeKalb County’s history.

The Black American story has been one of triumph, resilience and steadfast hope for a better tomorrow. However, despite these attributes, the push and pull of white supremacist ideologies has not missed a single city or town in America—and Lithonia is no different. Following the Civil War, these new American citizens of color were no longer viewed as a commodity and thus in many eyes, they became a threat to the socio-economic hierarchy that predated America itself. As a result, violent measures were taken to ensure that Black people understood their presumed “place” in this new version of American society. In efforts to drive this point home, lynch mobs began to spring up throughout the nation after Reconstruction and their actions left an imprint on the collective memories of millions of Americans until this very day.

A History Of Hate

Here in the historic City of Lithonia, the northern-most point of Arabia Mountain NHA, this horrid legacy leaves a trail that speaks to the time, the hatred and the small-mindedness of the hive-mentality that was all too prevalent during segregationist America.

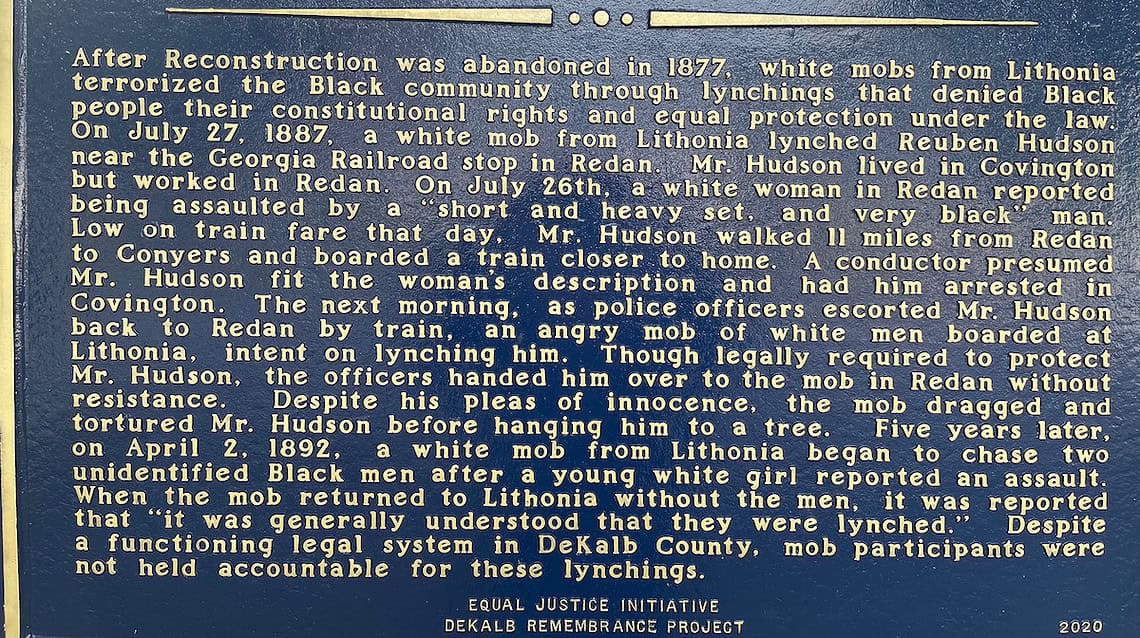

The reverse side of the historical marker in Lithonia’s William A. Kelly Park.

On July 26, 1877, Mr. Reuben Hudson, who was facing financial difficulty, walked 11 miles from Redan to Conyers to catch a closer train to his Covington home. His only mistake was being a Black man in the vicinity of an assault accusation from a local white woman. Since the unnamed woman only said that her assailant was a “short and heavy set, and very black” man, her speculation allowed for any number of men to be implicated. A train conductor felt that Mr. Hudson fit the minimal description and had him arrested upon his arrival at the Covington train station. The following day, after being escorted back to Redan from Covington, Mr. Hudson was handed to a lynch mob by the local police. This mob tortured and hanged Hudson despite the sworn duty of the police to protect him.

Other Nameless Victims

Similar incidents occurred throughout DeKalb County in 1897 when two unnamed Black men went missing following another white woman’s assault accusation. Sparse media coverage and even less police intervention or investigation led local media outlets to report the whereabouts of the two young men as, “generally understood that they were lynched.” With this being the general sentiment of the time regarding these terrorist acts, it is highly likely that there are several more unrecorded and forgotten lynchings.

The final recorded lynching in DeKalb County took place on August 21, 1945, when Mr. Porter Turner was found stabbed to death in the front lawn of a physician’s home in Druid Hills. Mr. Turner, a taxi driver who serviced white clientele, was later found to have been killed by members of the Klavalier Klub—a branch of the Georgia Ku Klux Klan. Despite DeKalb County having an active court system, no justice was ever served.

The Past Isn’t The Past

The Lithonia plaque was revealed in February 2021 and documented by the NAACP. This marked the third historical sign installed as part of DeKalb NAACP’s Remembrance Project, which has installed markers in North Druid Hills and outside the DeKalb County Courthouse in partnership with the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative.

These stories, while painful, are powerful reminders of the long-lasting legacy of racism and the crippling effects of white supremacist ideals. In this modern era, as the country gears up for its’ 250th anniversary in 2026, and DeKalb County concludes its bi-centennial celebration, it is these stories that need to be told in the spirit of Sankofa, the Ghanian act of looking to the past to make for a better future, because looking back will never harm us as long as we’re looking back in efforts to make the journey forward more equitable for all people. To learn more about these lynchings and the Equal Justice Initiative’s work to investigate and give names to the many nameless victims of domestic racial terrorism, please visit the historical marker in William A. Kelly Park in Lithonia on Max Cleland Blvd.