Never Before Told: Father Methodius Recalls Civil Rights Past And Meeting Dr. King

The 95-year-old monk at the Monastery of the Holy Spirit has led a fascinating life, including serving in WWII and marching with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

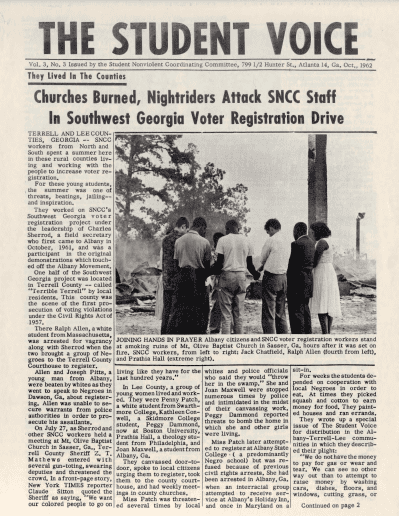

Sixty years ago, Father Methodius received quite the surprise. He found out that he’d been volunteered by prior Father Joachim Tierney to create 30 stained glass windows for 3 Black churches burned by the KKK around Augusta, GA in 1962. The churches had been targeted and firebombed in a campaign of Klan-orchestrated White terrorism and intimidation as retaliation for a summer of voter registration led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC vowed to rebuild, even getting baseball legend Jackie Robinson and the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to fundraise. The organization also contracted Atlanta architects and sought the closest stained glass maker they could find, which happened to be Methodius at the Monastery of Holy Spirit, a cloistered Order of the Cistercians Strict Observers (OCSO).

“I didn’t really connect it to Civil Rights at the time,” said Methodius, his eyes still sharp and azure like the blue stained glass shards dotting his work studio on the monastery grounds. “I was always into art, even from a young age, but I never looked at [stained glass making] as an art. It was just a job to be done.”

Heeding The Call

Born as Richard Telnack in Detroit in 1928, Methodius had already lived a full life before joining the

A sample of Methodius’ work from the narthex of the Christ Our Hope Church in Lithonia.

Monastery in rural Conyers, Georgia. By his early twenties, he’d studied architecture at Catholic University of America in D.C. and served as a Marine in Beijing during WWII. He also already had an interest in Civil Rights. On the way to boot camp after enlistment, Methodius stopped in Atlanta where he came face-to-face with segregation. “I got off the train in Atlanta and saw this big sign: ‘Whites Only’ and ‘Colored,’” he recalled. “And I didn’t like that. That’s one of the reasons I came to the Monastery in Georgia, because of segregation.”

A few years later in 1949, when he heard that the Monastery of the Holy Spirit was being constructed just outside of Atlanta, he packed his things from Detroit and took the next train heading South. At the time, only the foundation of the Abbey Church existed. “There were 21 monks at the time, most of them farmers and still living with a vow of silence,” recalled Methodius, who would soon put his architectural acumen to good use. “The architect for the whole building, when we were 22 feet, 4 inches up, had a nervous breakdown and I took over after that. I was on every concrete pour and I designed the original bell tower.” And when the new Abbey Church needed stained glass windows, Methodius stepped up, learning that skill from Atlanta-based Llorens Stained Glass Studio and later in West Virginia with the Blenko Glass Company.

30 Stained Glass Windows

An excerpt from a Southern Christian Leadership Conference newsletter dated March 1963 that refers to the MoHS as “Trappist Monks at Conyers, Georgia.”

So when prior Father Tierney, who’d been communicating with SNCC, told Methodius that he’d already been conscripted to construct 30 brand-new windows for the 3 destroyed African American churches, Methodius didn’t delay. Then-Abbot Augustine Moore permitted Methodius to travel to Atlanta to work with architects to determine the size of the windows. Splitting the duties with a coworker named Anselm Atkins, Methodius quickly built his stained glass pieces utilizing the same techniques and glass he used for the monastery refectory: simple rectangles that allowed for easy construction and painting of civil rights leaders and scripture figures: Jesus and the prophets. In short time, Methodius and Atkins finished all the windows.

In early 1963, Methodius, Moore and the Atlanta architects attended the dedication ceremonies for the new churches where Dr. King spoke. “I got to meet him,” said Methodius about his run-in with the Civil Rights icon. “I shook his hand and thanked him for being there.”

Civil Rights Legacy

That wasn’t the end of the Monastery’s social justice work either. According to the order’s oral tradition, during the height of the Civil Rights movement, Abbot Moore wrote letters to Dr. King about participating in marches. While Dr. King replied that Moore’s place was in the sanctuary, on his knees in prayer, other monks did march. In 1967, in his simple black and white habit, Methodius and monastic novice Stephen Gosselin demonstrated with 400 others, including Dr. King and Coretta Scott King, marching from Ebenezer Baptist to Georgia’s capitol steps. Methodius once again shook Dr. King’s hand. “When Dr. King came along he sparked something in everyone,” said Methodius. A year later, an assassin’s bullet struck down Dr. King on a hotel balcony in Memphis—his work left unfinished.

The monastery hasn’t been as politically active since those days. Six decades later, Methodius is mostly retired but still experiments with glass in his shop where hang several of his windows in blue, and black and white. Looking back on his 95 years, Methodius has a surprising take on it all. “Life is serious,” he said, “but don’t lose your sense of humor. [That] will see us through even the darkest times.”