Black History Month: Bruce Street Alum Mae Frances Anderson

Anderson is the last living member of the Bruce Street School graduating class of 1950 and her grandmother Frances Branham was a third-grade teacher at the school.

At 90, Mae Frances Anderson still remembers going to school at the historic Bruce Street School in Lithonia. Today the stone schoolhouse, which was DeKalb County’s first public school for Black people, lies in ruins, the focus of a multi-million dollar revitalization project spearheaded by the Arabia Alliance. While the edifice might be quiet and fenced-off these days, back when Anderson was a student there, it was the bustling center of Lithonia’s Black community, where parents, children and educators all converged over one thing: the importance of Black education in the Jim Crow South.

Last Of A Class

Anderson is the last living member of the Bruce Street School’s graduating class of 1950. She’s also one of the last years to graduate from the stone schoolhouse as it closed in 1955 when the State of Georgia, in an effort to avoid integration, built “equalization schools” across the state. This included one across the street from the stone schoolhouse that became the new Bruce Street Equalization School (currently the Lithonia Police Precinct). Anderson had deep ties to educators in the area. “My grandmother [Frances Branham] was my third grade teacher, and also my aunt was a teacher in the DeKalb County Schools,” said Anderson. “It was expected of me to be a good little girl and make good grades.”

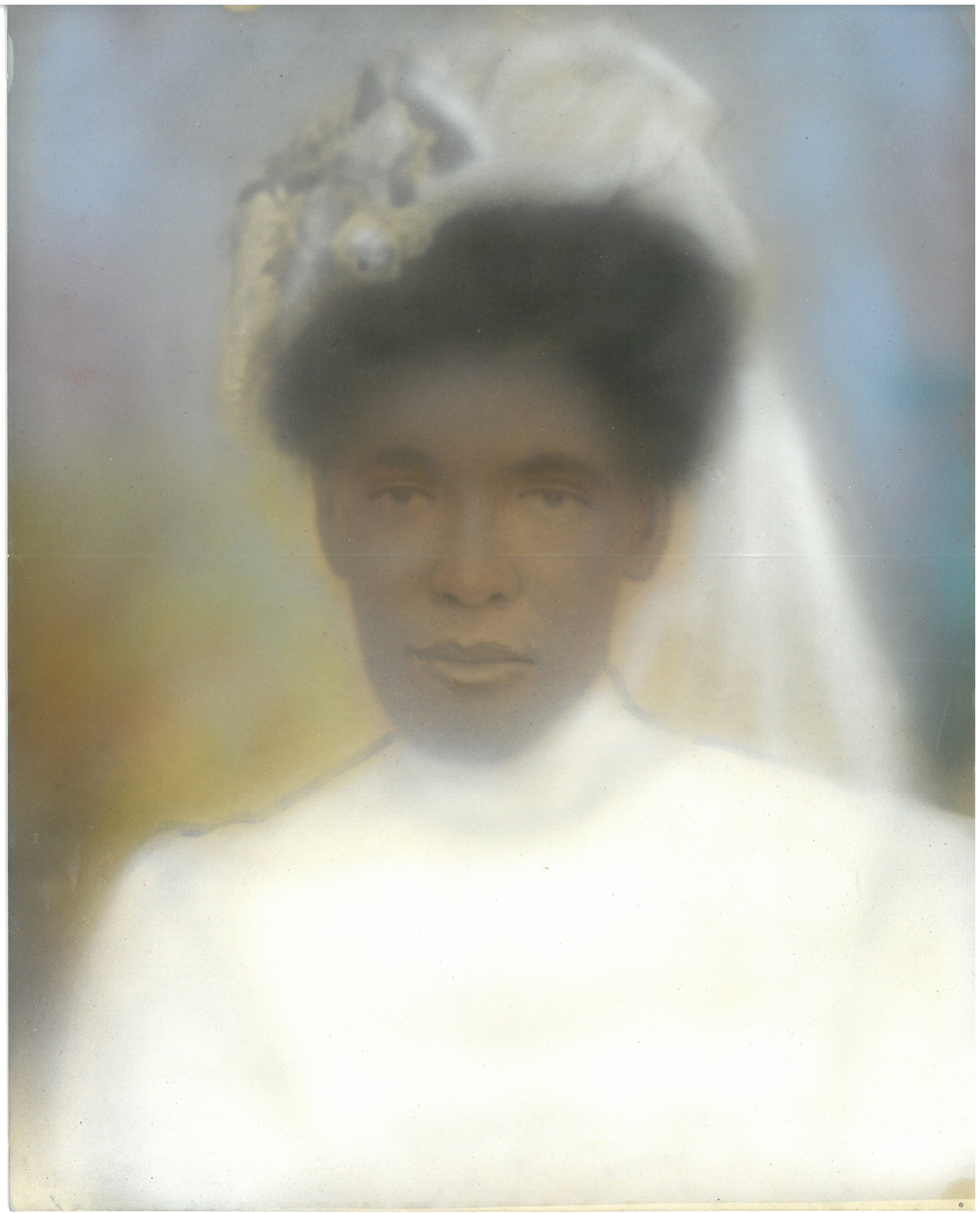

Frances Branham’s wedding photo.

Anderson’s grandmother Frances Elizabeth Haygood Branham was a respected local figure. She’d been the principal of the Yellow River School, burned down by the Klan according to oral history, and later taught at the Bruce Street School from 1941 until 1944 when she passed away. “Her brother Nathaniel Haygood had a doctorate,” said Anderson. “Can you imagine: a Black man in those days having a doctorate? That’s unheard of. I was expected to live up to that and make good grades.” In one remembrance from the 1995 reunion brochure from the class of 1950, one alum wrote about Mrs. Frances Elizabeth Haygood Branham: “Always order in her class, enforced by those long switches.'”

Although Branham did not live to see Anderson earn her diploma, she would’ve been proud to know that she graduated valedictorian from her 1950 class of eight.

Bruce Street School Class of 1950, from left to right: Henry Harper Hall, Mae Frances Branham, Erma Isabel Lyons, Mariah Leslie, Dorothy Mae Allen, Agnes Scales, Julia Mae Jonson, and Betty Gypsy Smith.

Life As A Bruce Street Student

During the days of Jim Crow segregation, Black schools had to get by with far fewer resources and public funding than White schools. This was evident in many different ways to teachers and students alike. Anderson remembers that the respected principal Coy Emerson “C. E.” Flagg was also the school biology teacher. When it came to finding specimens, Flagg had to get quite creative.

“Mr. Flagg sent a couple of the boys to get some stray cats, and the girls thought we don’t have to worry because the boys will have to kill the cats,” recalled Anderson. Not so! “Each girl and boy had their own cat. It was horrible. We killed the cats–we had to boil them and skin them, clean the bones, and make our own specimens. That afternoon I went home from school, my mother had made some kind of soup. Can you imagine, your mother expects you to eat some soup and all you can think about are those dead cats being cooked?”

Another alum wrote in the 1995 reunion brochure from the Class of 1950 a remembrance of C. E. Flagg starkly stating: “The skinned cats and pickled rats in Biology.”

Biology class aside, Anderson says she has mostly good experiences from the old stone school. In particular she remembers the sense of community and spirituality during Friday assemblies. “We had assembly and we pledged allegiance to the flag and you said a prayer,” she said. “Everybody went to church on Sunday. So being able to pray and do the pledge of allegiance, that was wonderful, that was a way of life. Real pleasant memories of those times.”

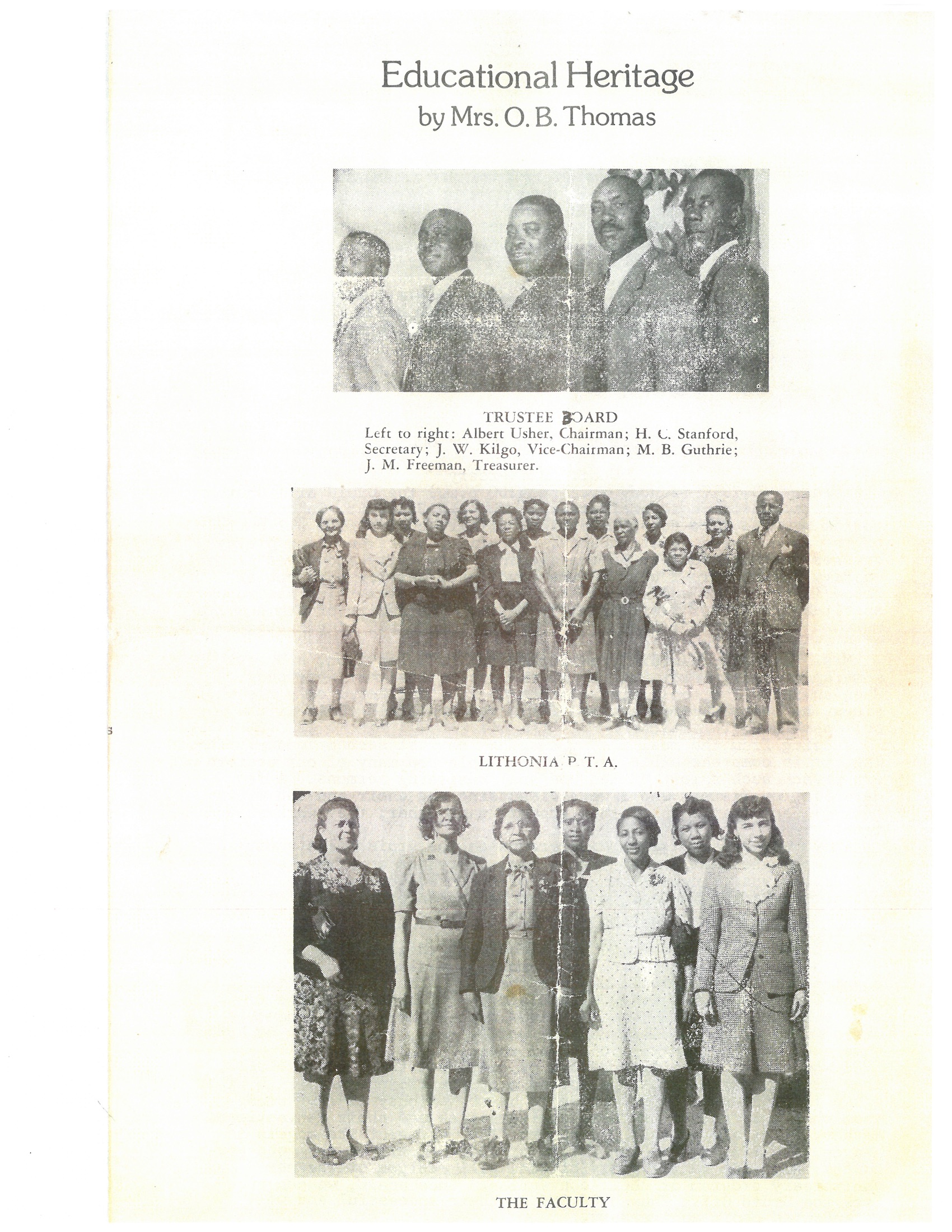

Faculty and Staff of the Bruce Street School circa 1950.

Life After Bruce Street

After graduation, Anderson took a course in practical nursing at the Beaumont School of Nursing in Atlanta. She worked sporadically caring for mothers and their new babies. In August, 1953, she married Thornton Anderson, her high school sweetheart and the son of another Bruce Street icon, Miss Ada Anderson, the historic school’s master cook, who fed a generation of school children and taught many her culinary secrets.

Miss Ada Anderson.

Frances Anderson and her husband moved to Philadelphia, PA, where she gave birth in September, 1954 to their only child, Cynthia Arlene. Five years later, Anderson began what would become a long career with the Federal Department of Defense. For the first four years she worked as a clerk stenographer, but soon climbed her way up to management positions, spending the last 23 years of her 31-year career as Budget/Program Analyst with the Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery System. “This position involved procuring equipment for and inspecting veterans’ cemeteries,” wrote Anderson in a remembrance. “This was quite a departure from my upbringing since, as a child, I was afraid to walk past a cemetery, especially at night.”

This work took Anderson around the country, visiting veterans’ cemeteries in Virginia, New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, Michigan and Philadelphia, among others. “My familiarity with cemetery regulations and policies enabled me to obtain burial space and headstones for friends and acquaintances who were unaware of the many benefits available to veterans and their families,” wrote Anderson.

After retiring in 1990 and her husband retiring in 1993, the pair spent years traveling together across much of the country and parts of the Caribbean and Canada before moving back to Lithonia in 2001. Today, Anderson lives across the street from the very house she grew up in, and only about a mile from the Bruce Street School ruins. Thanks to a community-funded, grassroots effort lead by the Arabia Alliance, those ruins will soon be transformed into a community outdoor museum with an amphitheater, food forest and historical interoperation about Black education in the Jim Crow South featuring stories like Anderson’s own.